The Roe v. Wade decision has been tugging on my writing conscience as a topic for Mayhem. But I have to tell you all, I am so tired of being angry. I am tired of my consternation about the one step forward, two steps back for women in this country. I am tired of being heartsick about the lies woman continue to be told about their places in this world.

I wrote about this after the leak of the Supreme Court opinion weeks ago. If you want, you can read it here. I am worn down by this. I have nothing to add.

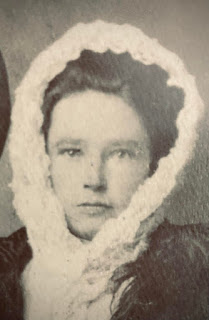

I have been thinking for the past few weeks about my grandmothers, who grew up at the turn of the 20th century, one in Louisiana and one in the Indian Territory that became Oklahoma. Octavia, my maternal grandmother, was one of eight children. Nan, my paternal grandmother was one of seven children.

I have been thinking about my life compared to theirs, and how even though I wasn’t really close to them as a child, physically or emotionally, they had great influence on me, even if I am only slowly discovering how.

I observed them more from a distance, visiting once a year on our family vacations in Shreveport, La., or Sulphur, Okla., from wherever my Dad was stationed in the Air Force. I did spend a year in Shreveport with Octavia in seventh grade when my dad was in Turkey.

Louisiana was an unsolved riddle to me, with its parishes instead of counties, oily black streets, trees draped with Spanish moss, and row after row of shotgun houses, one-room wide with couches on the front porches.

Octavia, a registered nurse, lived in a one-bedroom wood slat house planted firmly on concrete blocks. Every room but the kitchen had a bed: a narrow bed with a feather mattress on the front sleeping porch, a double bed with a high headboard in the actual bedroom, and a high off-the-floor iron framed double bed in the living room, where Octavia slept on two mattresses, one with blue ticking, one with pink, that hung over a smaller box spring.

She had lived alone for decades, divorced when her children were young, and without further interest in men, it seemed. I have only recently come to know through the magic of the internet, because my family never, never spoke of him, that Octavia was my grandfather’s second wife of three, and that he had a son from his first wife that he fought for in the courts and lost, then had two sons and my mother with Octavia.

Octavia attended a small fundamentalist church – no organ music, fire and brimstone preacher -- twice on Sunday and on Wednesday nights, where she would sit religiously in the same pew, right side middle near a window. She wasn’t much of a hugger, but occasionally she would plunk a shaky hand on my dark brown hair, and I would feel anointed.

My grandmother didn’t talk much. When she did, the words seemed to rumble up from her bowed legs, move slowly behind her ample bosom and hang in the air for long minutes.

On the occasions when my cousins and I would spend the night, she would serve us eggs from the rickety hen house in the corner of her backyard, and for lunch a slice of ham, black-eyed peas and okra. A few times, I had seen her shuffle down the back steps, grab a reddish brown hen from the yard, and pop and cleanly sever its neck with her bare hands. The headless chicken would run around the yard, colliding into whatever was in the way, spattering blood until finally collapsing. She would then bring it to the kitchen for plucking as I watched from across the room.

My paternal grandmother Nan was born in Cherokee Nation and then moved from small town to small town with her family, her father a doctor who worked out of his house, getting paid with whatever the patient could spare. Nan, the youngest, spent a lot of time helping him, all the while dreaming of a real education, and being somebody important who would do interesting and exciting things.

My aunt, who wrote a biography about her, described Nan as overflowing with enthusiasm. Her siblings had plenty of names for her, like smart aleck, baby, dreamer, and “too big for her britches.”

At 19, when she first met my mysterious, good humored, rambling, handsome grandfather, she spent a year or more in angst, “teased with the prospect of love and marriage and smothered by the thought of confinement and drudgery.” She couldn’t come to terms with giving up on her determination to get an education.

In the end, she surrendered to love and never got more than a few months of formal education. She spent her adult life the wife of an Oklahoma “dirt farmer.”

When I was a child, I wasn’t interested in knowing my grandmothers on more than a superficial level, observing only what was in front of me. As a grandmother myself, I now have many questions I wish I could ask them.

Nan died when I was 12, when my family was stationed in Arkansas. I stayed home with the mumps while she was being buried in Oklahoma. Octavia died when I was 22 and away at college. My mourning was more for my father and mother at those times, and their grief of losing their beloved mothers.

I am still learning about these two women from my far past, about Octavia in bits and pieces with the miracle of the internet and Nan from the gift of those two biographies. I can see now what they passed on to me, how they helped to mold who I am today.

I used to think they lived in simpler times. Not true. Octavia was a nurse during the 1918 flu pandemic, while also mothering a 1-year-old and a 3-year-old. She became a single mother when they were still young. Nan also lived through the pandemic, in addition to the devastating dust bowl in the south plains while farming. They both endured two world wars, with sons fighting in World War II, and neither could vote until they were in their 40s.

I keep thinking of the comment that Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did … but backward and in high heels.

Just as my grandmothers knew, they can throw challenge after challenge at our feet, and we will keep moving.

But please, this time, not backward.